AI ate my GIS

AI is making maps, but who will make the maps for AI? As interfaces of computing evolve, our community should position itself for success. Otherwise another industry will eat our lunch, again.

GIS is a data exploration tool.

A year or two ago, I came to the conclusion that GIS, as a technology, is a convenient environment for data exploration. It’s best for data with a geographic component, and GIS provides the helpful feature of showing that data in a cartographic manner. But really, this is just a data visualization option, a map. One can also interact with aspatial data, as we call it. Or data without a spatial component. In GIS-land, we have a name of data that GIS can’t natively visualize, which, counter to popular geospatial opinion, is most things. Unironically, outside GIS-land, aspatial data is just data, and spatial data is just data. In many ways, this relationship is comparable to the “Venn of Geospatial People”. But semantics aside, GIS is useful for analyzing spatial data; it’s handy for getting a visual check of a data product's quality, scale, and “look.”

Wait, I’m already logically confused. I confused analysis with visualization. These are two different activities; as geospatial people, we can conveniently conflate them. As an analyst, I want to ensure the data I am using is fit for purpose. That trust-creation process supports the analysis but isn’t necessarily part of it. Traditional GIS excels at that trust-building process. Unfortunately, it’s actually bad at running analysis at scale. Hence, the proliferation of “accelerated geospatial” companies. My observation is that if GIS were good at scale, there wouldn’t be a market for “more scalable” technology. This is the basis for my observation of GIS as a data exploration tool: it is designed for the one-off exploration of one or more data products and for examining the results.

So, GIS is an excellent tool for visualizing spatial data products, often to tweak, refine, or build trust in those products. The data, once confirmed as authoritative or indeed “good enough,” is published for use elsewhere. I agree with this workflow. Data should be taken to a point of confidence, then published for use by broader systems. This speaks to two of my regular talking points:

1) That geospatial is a deep horizontal, and

2) That, while investing in technology is like buying a car, investing in data is like buying a house*.

Unfortunately, confusion has arisen about the boundaries of GIS as a practice. An argument that I have no energy for now, suffice it to say that the siloization of GIS practitioners has not been good for the geospatial community at large (notably, but not exclusively, in terms of employee compensation and technology integration). But I also think that the GIS practitioner, who might see the map as their product, is facing a deeper problem: personal software.

Personal software

I’ve built two or three applications this month. I can’t remember the actual number because I don’t have them anymore. I built them because I needed to see something or scratch a particular technology itch. I default to Claude Code because that’s what we use at Sparkgeo. But really, it could be any AI of your choice. The point isn’t which AI; the point is that I, the CEO of a small company with a technical background who is probably now “the worst software developer in my team,” am building apps. Those apps I built might last 15 minutes or 15 years. They might be handy or just silly.

An Aside…

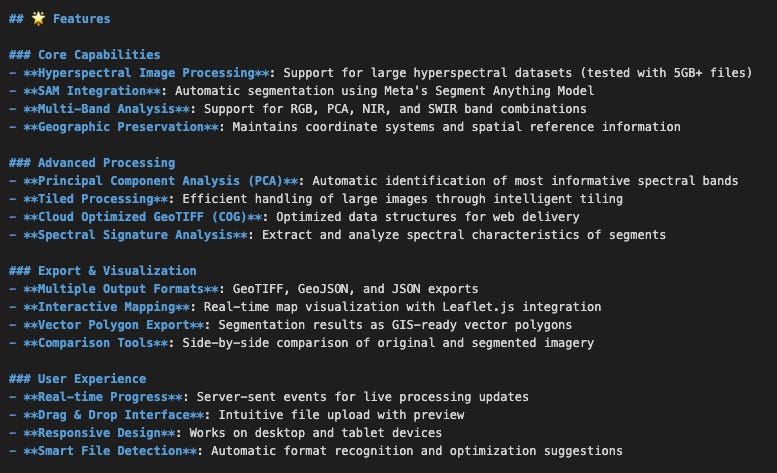

For the Earth Observation geeks in my readership: I built an application to recieve a dragged hyperspectral image up to 5GB, then tile appropriately for visualization, then apply a PCA analysis to the bands of the image which are typically outside the wavelengths detectable by the human eye, then run Meta’s “Segment Anything” algorithm over the result and show the original image, the PCA output, and the Segment Anything output as three layers on a slippy map for visualization. The idea being that I was building a visualization of our invisible planet. Well, invisible to us humans. A fun little art project.

This took an hour or so. There is something about the dopamine hit of building something. It’s worth reflecting on the addictive nature of this kind of accelerated building. Too much dopamine too fast is probably unhealthy.

While art projects are fun, this is also an interesting data point: this would have taken me forever to build previously. In fact, I probably wouldn’t have bothered; it would have just sat in the back of my head with a bunch of other ideas getting rusty. But with the right tools, it took me just an hour or so; I satisfied my curiosity and felt like I “built something.” And that dopamine flowed…

Tell me the time

I heard a wonderful analogy last week at the NASA Earth Science & Industry Summit in DC, credit to Christine Wallinger, who I suspect might further reference her university professor:

“We show people how to build clocks, but they just want to know the time.”

Traditionally, we have provided extremely complicated tools to build perfect clocks. And people do care that their time is correctly kept. But a barrier to the adoption of geographic tools is that business people don’t want to build clocks, or have a team that builds clocks for them every time they have a geographic question. In the last two weeks, I learnt that those clocks can be built and discarded with so little fuss that, in many ways, user interfaces have become ephemeral.

The previous week, I was having coffee with an AI researcher from a notable AI company at a lovely Chilean coffee shop near Paddington. As the crema of my coffee slowly dissipated in the cool air, he showed me a workflow his team had built in real time for a government customer. While there was nothing groundbreaking in terms of geospatial and mapping, clearly, this was an application one would describe as a GIS. The workflow had placed points on a map and used them, along with their attributes, to create a least-cost path. Those points were sourced (by the AI) from a specific open data source, and the mapping fabric was open source as well. So, in delivering a traditional GIS product, the AI had happily created a satisfactory experience for the government customer without touching any traditional GIS technology or any explicit geospatial expertise.

Bring it on, feel free to yell

You could say “lack of authoritative data!” or “AI slop!” or “cartographic incompetence!” and you could be right on all counts. That’s not my point. This was not a good map, but it was adequate. My point is about the definition of “good enough” and the disruption that occurs when an underserved market encounters a low-cost product. That underserved market could be the deep geospatial horizontal referred to above, and the low-cost product could be prompt-driven AI.

The question here, then, is whether this new geospatial market will be served by traditional geospatial technology companies or by others. If we remember, Google Maps was created by a web search company, not a mapping company.

So, if we are in the end of days for SAAS applications as the markets are suggesting (SAASmageddon!), and AI will eat the world, as various billionaires will insist (all who have a financial interest in AI eating the world, I should point out). Then where does that leave the geospatial sector? Where does “authoritative custodianship” come into this debate? Have we forgotten to care about data and maps? Who will be designing the maps of the future? Who will sweat over label positions? Who will worry about scale effects in data misrepresenting a particular feature? Who will tell me they don’t like pink on their maps (hint: apparently, middle-aged male foresters, at least they didn’t in the 2000s)? Will AI slop insist that the great circle route is not the fastest way across the Atlantic?

No. Precisely no. In fact, that is the point: we can be comfortable in the fact that our user interfaces will change, and they should, yet data still has an intrinsic and increasing value, and we can extract more and more meaningful analytics from that data. But we will have to think about geospatial service delivery differently, and that shift will come with new business models. If we are very lucky, that change in model will bring greater access to the deep geospatial horizontal market I keep talking about. Ultimately, enabling a much broader array of businesses to use geospatial technology daily at a lower cost.

If we were to summon some optimism in a time of undeniable cynicism, we could see a resurgence of geographic capability and use, because it’s easy.

Where are the geospatial experts?

This future may seem bright for the multitude of non-expert users, but what about those people who used to make maps? Well, for a long time, they still will. The future is, of course, unevenly distributed. As there are still fax machines and people who make horseshoes, mapping will remain a skill. But interfaces will change, fast for some, slow for others.

But for those looking to engage with a new market, we will need to ensure that data products are authoritative, accessible, secure, and consistent. Additionally, we should be building componentry that AI technology can assemble into convenient user interfaces. That componentry should provide the algorithmic or geographic rigour to put the minds of the most fervent geodesists at rest. The components should allow non-experts to assemble geographic experiences without worrying about the complexity of clock-building, while knowing that experts have ensured quality, and to assemble their data products to tell their time with ease.

If it doesn’t or we don’t, then we will have failed, and again, we will have let another industry eat our lunch.

*I cannot believe I haven’t talked about this subject, but it’s true: data accrues value over time like a house, while technology depreciates almost instantly. We will dig into this more when I write a note about this core Modern Geospatial concept. Watch for it in future posts.

.

![Request] How much more would this cost an airline? : r ... Request] How much more would this cost an airline? : r ...](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KCh2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0193a31d-747b-44eb-a8a7-33c9673dd5d9_640x692.jpeg)

Hey Will, this is a good shakeout of the now, and near ... challenges abound, and the path is a winding one for sure ...