Domineering an alternative reality

Dominant designs and the adjacent possible

Hey team,

Thanks for sticking with me this far. So far, we’ve talked about why being strategic is useful, and we touched on the resource-based view, an internal form of strategy development. From this point on, I will lead these discussions more toward understanding an innovative environment. To do that, we need to understand and agree on a few core concepts. Today, we are going to talk about dominant designs.

Dominant designs

Why do cars have four wheels? Why is the engine almost always at the front of a vehicle? Why do almost all pens and pencils start the same length (pre-chew and sharpening)? Who chose all this stuff? The answer might be: we all did, or at least the market did.

A dominant design is an accepted form. Now I have mentioned this concept, you will see examples of these everywhere: laptops, cellphones, beds, food containers, home appliances, cars etc. Almost every human-designed object has been engineered and re-engineered to reach an accepted form. They are everywhere. In fact, dominant designs are an intrinsic part of an innovation process, usually the end part.

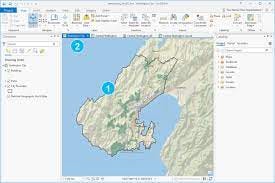

This concept is important because it tells you a story about a product’s development. It tells us when a design has become broadly accepted by those who use it. Clearly, these patterns can be seen in software and in particular in Geographic Information Systems (GIS, sigh an acronym):

I think it would be reasonable to argue that GISs followed the typical pattern of menus at the top, etc. But, we like our layers organized on the left with the map on the right, and perhaps some extra context floating on the far right. I think we can all agree that the “form of GIS” has been solved. They all pretty much look the same, with more or less user interface polish.

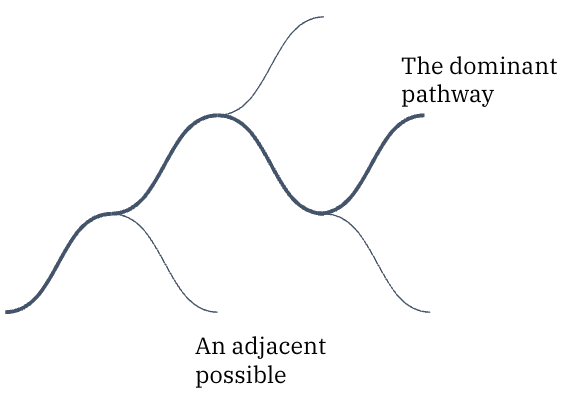

The problem with the dominant design is that once it has reached a point of acceptance, it can become a barrier to further innovation. Once a design is dominant local maxima can be achieved (the greatest performance of this design), but it is very hard to break from the accepted design to search for the global maxima. This is especially concerning when surrounding capabilities change (we will take a look at the critical concept of “complementary assets” in future discussions.) So if a dominant design is such that it cannot make use of new technology, that might be a local/global problem. An obvious example might be desktop GIS being unable to meaningfully leverage cloud resources. This is being alleviated to some extent with “hybrid” approaches, but this does seem a little square-pegish (not a word, I know.) I am sure you get my point: dominant designs can become mental and physical barriers to innovation.

The adjacent possible

But who chose that way and why? And is there a good reason for us to continue to accept it? Now, I am not advocating for longer pencils, but I am advocating for taking a second look at the most obvious of products around us and questioning their utility.

Was there a point in a product’s development when a different design decision could have been made that would have resulted in different capabilities? This is one consideration of the adjacent possible.

If any of you saw the Loki TV series, the way that team considered how timelines could split is a great visual to describe product development paths. In some ways, the concept is very similar. At some point in time, a decision was made for a product to “look this way”, or “do that thing”. Your job as a curious strategist is to wonder:

1) Why?

2) Was that decision good or bad (within your context)?

3) Can/should you do anything about it?

These questions prompt a mental review of whether the dominant design is in fact still fit-for-purpose within a modern context. More to the point, considering the adjacent possible challenges us to think about what could have been, which immediately prompts us to consider if there is anything obvious missing now.

The missing designs

I would argue that modern geospatial is in a unique place. For reasons that I will discuss in the coming weeks, we have a dearth of dominant designs and that is both a tremendous problem and a wonderful opportunity.

Yes, I completely agree that the most common data exploration toolkits: GIS, PANDAS, R Notebooks etc, are well understood and dominant designs have been agreed upon for some time. But the application of modern, scalable geospatial technology to the commercial sector is deeply misunderstood. I believe we will see a slew of new designs emerge for different geospatial solutions in different markets and these will be less map-centric than we are used to (watch out for the Fallacy of Obviousness in future discussions.)

Why? Because our available complementary assets have evolved enormously and as a result, our capabilities have quite suddenly, yet quietly expanded. We can do so much more, but few know the extent of the possible. Exciting times.

Next time: Complementary Assets

PS

I've always enjoyed Edward De Bono's lateral thinking strategies. One of which is "yes, no, po", po being "provoking/provocative operation", a way of considering the unconsidered and being able to move your attention away from the accepted norm.