Custom Inc.

In the modern product-driven technology landscape, services revenue is often viewed as problematic. So why, in the geospatial community, are services-led companies so much more successful?

But first, this, North51

Hey, perhaps you haven’t heard, but North51 is coming up in January. This is the geospatial thought leadership event. If you haven’t been before, you should take a look. If you have, you know what to expect, except this time we will be deep in the Canadian winter, and we have some great deals with the local ski hills.

Something a little bit special?

The geospatial community is full of old companies. While I don’t feel Sparkgeo is terribly old, certainly not in comparison to venerable organizations like the UK’s Ordnance Survey or Swiss Topo (Switzerland’s Federal Office of Topography), or even Esri, the leading pure commercial organization, I do feel we’ve “been around the block.” One of the reasons we’ve stayed in business is annoyingly counter to almost all the advice one might hear in the typical technology business circles. Geospatial, as a practice and at scale, is almost always a little bit custom and custom business activities usually demand a services team.

What’s wrong with services?

Services revenue isn’t scalable. That’s the oft-repeated mantra. Software is scalable, you can build once and sell many times, and services are linked to “billable hours,” so one can only scale with more FTE’s. On an exceedingly simplistic level, that’s true. Except that nothing in life is simple, and business mirrors life.

However, let’s take a quick tour through the generalities. When considering services versus product companies, products tend to attract a higher exit value, which, for lack of a better metric, is the central perceived business value: what someone would pay for that business. There is an inherent bias in this statement, as most valuations are driven (reasonably) by investors seeking a return on their investment. In contrast, most service companies don’t need investors. Interestingly, this implies that future revenue is more valuable than actual revenue.

However, the central point here is that the typical investment community views a services component in a company’s revenue stream as a dangerous path to a reduced unit economy. Their “build once, sell many times” mantra is diluted by any billable hours of services tinkering. Worse, if the company in question is publicly traded, and the market views its revenue as consulting or services, then the share pricing implication could be disastrous.

This has led to a situation where new geospatial companies are motivated to be viewed solely as products, and not as services. Yet, in almost every occurrence of the GIS or geospatial experiences I’ve had, very little is genuinely repeatable. Yes, we will use the same tool, but to do different tasks. I would argue that traditional GIS is essentially a data exploration environment. When GIS analysts discuss automation, it is usually in terms of automating an activity for multiple records, rather than supporting many users performing a repeatable activity. Perhaps this is why GIS companies have struggled in consumer-web environments?

Let’s get physical

Our world is a complex system, and when we attempt to model it, the patterns are not typically reusable. Think about car counting. We can count cars in the Port of San Diego from Earth Observation data. But that algorithm will not work well in the Port of Dalian in China. There will be differences in atmospherics, differences in parking patterns, and differences in vehicle types. So the algorithm must be tweaked. This is true of most Earth Observation practices. While we hope that geospatial foundation models will resolve this problem, it persists today for those seeking robust, production-level accuracy. So, who does the tinkering? Consider languages for user interfaces in mapping, various addressing styles and cultures, and different search styles for different types of mid-morning drinks. Who does that work?

There is something about the interface between the complexity of physical geography and the complexity of human geography that, when combined, results in most geospatial platforms being generally applicable everywhere (see the geospatial product trap) but not being easily applied anywhere.

As a community, this profound physical-human complexity has always been difficult to articulate, yet it is something that most practitioners know and have experienced viscerally. In many ways, this is the surprising art of geography, why many of us remain joyfully curious about our world and its evolving systems.

I’ve come to consider geospatial as similar in nature to Artificial Intelligence, in that it is almost always the component of an answer to a question, but rarely the entire answer. As such, I think of geospatial as a deep horizontal. However, the critical extension to this observation is how one combines geospatial technology or data into other interfaces to provide a fuller answer. It’s all about interfaces, some digital, some human. While we can always get better at APIs and open (but secure) standards, and we should, those human interfaces are usually developed by physical people in services teams.

Yet still, there is a long list of companies that tried to execute without a services strategy but failed. And another list of companies that insisted on chasing the next project, thinking they were seeking product-market fit, but should really just have committed to being a services team or a services-led product, by building margin and project management into their services business.

Services-led geospatial

The solution, as I see it, is to commit to the obvious. New geospatial product companies, whether they be data products or software tools, should be comfortable with the idea that services are necessary. That idea needs to be seeded early with any investors, so arguments against the inevitable pushback can be prepared. In many ways, the controversial yet successful company Palantir has employed the “Forward Deployed Engineers” model for almost a decade. This is just a rebrand of a services-led technology product strategy. It is also worth noting that Esri (link above) also has a very robust consulting team, and each country-level organization is, in effect, a reseller and localized services provider. This model has become contentious among some, being perceived as somewhat anti-competitive, but it remains hugely successful.

Having a geospatial tool wrapped in services means that the customization component can be executed while the product is also being sold and developed. There are now two sources of revenue allowing for lower levels of initial dilution, and potentially a more agile product-market fit process. This also benefits the services team as their revenue becomes less “lumpy.”

Finally, it would also be possible to sell this structure more easily as a managed service, ensuring that there are people more closely attuned to how a customer is using or wants to use a product. Hopefully, this model will build a better product for all.

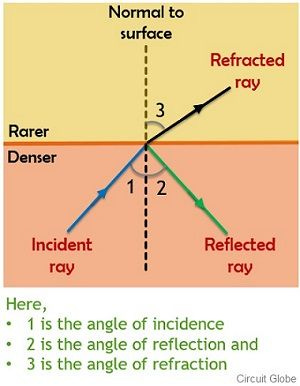

Don’t reflect, refract: time only goes one way

This is the time of year when everyone talks about what happened in the last twelve months. While your experiences do matter, time only goes one way. So, don’t get caught reflecting too long; instead, use your experiences to build forward and through; refract your experiences.

Great post, Will!

With Fulcrum, it was born out of a services need, and for a long time straddled that services/product divide. We started out pure self-service, attempting to minimize the need for consulting – to "build a builder" that would empower users to create for themselves. They'd be their own services provider and implementer. That approach gave us a foundation of inbound users, but even customers who *can* self-build don't always *want* to. Then there's, as you say, that healthy chunk of em with a bespoke problem that warrants some surgery to understand and solve.

The stigma of "services" revenue stems from the investor valuation mindset as primary business driver. I get that forward revenue is one of the best metrics for valuing a business for a buyer, *if* the objective is to hold and eventually sell.

But the simple-minded aversion to services misses a huge benefit of the product/services hybrid: services give you superpowers for deep understanding of customer problems. I experienced this firsthand, and believe it more each new business I see. It's uncommon to see it given the proper attention it deserves because it's hard to make its value legible to a financial-focused investor. The benefits of inside domain knowledge and human relationships to product innovation are underrated, different from company to company, and hard to model due to this illegibility.

What's even worse, though, than being either product or services focused is how the anti-services bias tempts businesses to muddy the water and cosplay as product businesses. The best thing you can do for your company is be honest with yourself about where your value lies.