Lament for the lonely pixel

How many pixels are captured but never looked at; how many pixels could be captured but aren't?

Captured by a CCD in the sky,

Never looked at by a human eye.

There is something enduringly melancholic about mechanisms that run but seem to have been forgotten by people. The obvious Hollywood example of WALL-E strikes a chord, leaving the viewer to wonder what happened to the people on the empty planet. Today, we can see these systems now around us. Remote environmental monitoring projects, IoT networks, and some vehicles can be doing things for long periods independently of human input.

Those building space systems are used to engineering “lonely technology.” Things that just keep operating independently until some mechanical failure. Indeed, there are numerous examples of machines communicating with machines, making rudimentary decisions based on no human feedback.

This is the kind of thing I think about as I run about the woods near my home; please don’t judge.

However, this is a surprisingly important subject for the Earth observation (EO) sector, and there are a few aspects to unpack. Firstly, not all sensors are designed to collect all the time. Secondly, even if sensors are designed to collect the entire time, there are limits to the amount of data that can be downlinked. Thirdly, how is that data stored for use, by whom, and under what license? Finally, how much of that data gets looked at? The extra credit question is, how can we increase this?

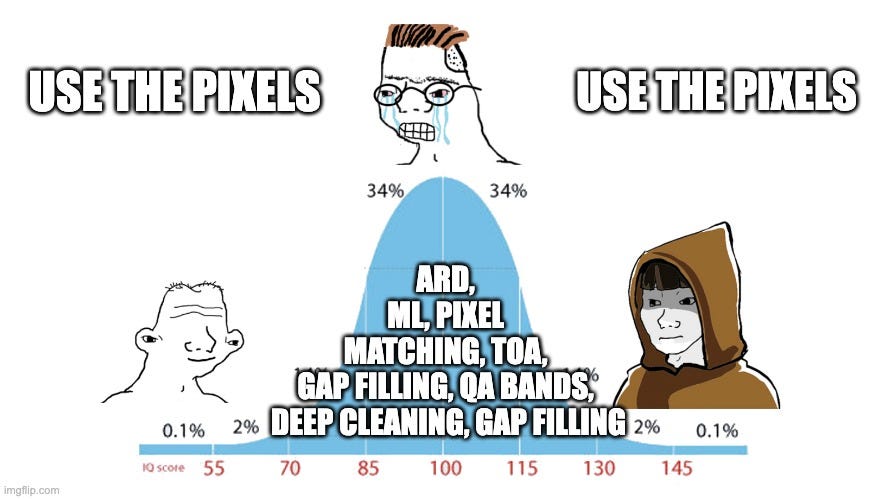

Expectations of EO have always been complicated. Even experts get mixed up in the specifics of sensors and orbits. It’s easy to say there are a gazillion sensors and they are all capturing data at a furious rate. But it’s intellectually lazy not to qualify that with “but they are almost all different.” Yes, I have often been intellectually lazy. Even more frustratingly, for the average EO practitioner, all these sensors are not easily compared. Playing my role as the white rabbit of geospatial, I will now encourage the brave reader to dive into the deep dark hole of “Analysis Ready Data.”

Hopefully, you will return. The point of this sidebar is to point out that almost all sensors are different; even if they are not supposed to be, they often are. The main point is some sensors are ‘always on,’ and many are ‘tasked.’ Both kinds can capture as much data as their varying storage capability allows within the context of the available downlink.

Downlink is still mainly a radio comms activity. There is some excellent innovation in laser and peer-to-peer options, but for now, we are mainly limited to radio methods with antennas perched on ground stations, typically in the Arctic or on AWS data centres. So the EO game becomes: “What are the highest value targets to be imaged and stored between different downlinking opportunities?” In effect, that is the optimization problem of every tasked EO satellite or constellation. Simpler sensors just capture as much as they can between downlinks. Sometimes, additional capacity is available and imagery captured; sometimes (usually when there are wars), imaging capacity is booked up.

Even when these satellites are booked, and data is flowing, there is no guarantee that imagery will be examined. As I pointed out lazily before, there are gazillions of sensors (say, 2-3 thousand) in the sky. The potential data flow from this silent armada is enormous. There are simply not enough expert eyes to look at this data. Additionally, sometimes data is overtly captured just so others can’t look at something or task a satellite at a particular time.

These patterns result in a deluge of data that simply remains neglected: The Lament of the Lonely Pixel.

How many petabytes of imagery have never been put to work?

In no uncertain terms, the solution to this problem is simple. More commercial or even consumer applications for EO. Additionally, geospatial foundation models will play a role in the holistic use and uses of EO data. Perhaps for the purposes of pixel loneliness, a digital eye is as good as a human eye; it’s 2024, who am I to judge?

The point of this slightly weird anthropomorphization of imagery is to create a visual in your mind’s eye of the digital exhaust of Earth observation. This is a byproduct we can and should put to work. I look forward to the day when we have the demand to consume any excess tasking capacity and the software to pull value from every pixel.